How a 28-year-old geologist made the biggest discovery of his career

It’s been 30 years since the first drilling began at the Pebble deposit in Bristol Bay. Pebble Watch interviewed Phil St. George, who is credited with discovering the significant copper, gold and molybdenum resource.

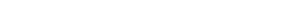

It was a cloudy day in 1987 when Cominco geologist Phil St. George – just six years out of college – first touched down at what would become one of the most well-known mineral prospects in Alaska. He’d been tasked with managing an exploration program looking for gold and copper in the Alaska Range, from Lake Clark to the Mount Hayes area further north. But the weather that day scuttled his initial plan to check out the Lake Clark quadrangle. The fog was in, along with low clouds that made flying there too risky.

St. George had seen some color anomalies in a nearby area a few years earlier and had been itching to check it out. Looking for rust colored earth is one of the simplest prospecting methods, as it gives clues that oxidized iron might be present. And that could also indicate the presence of gold.

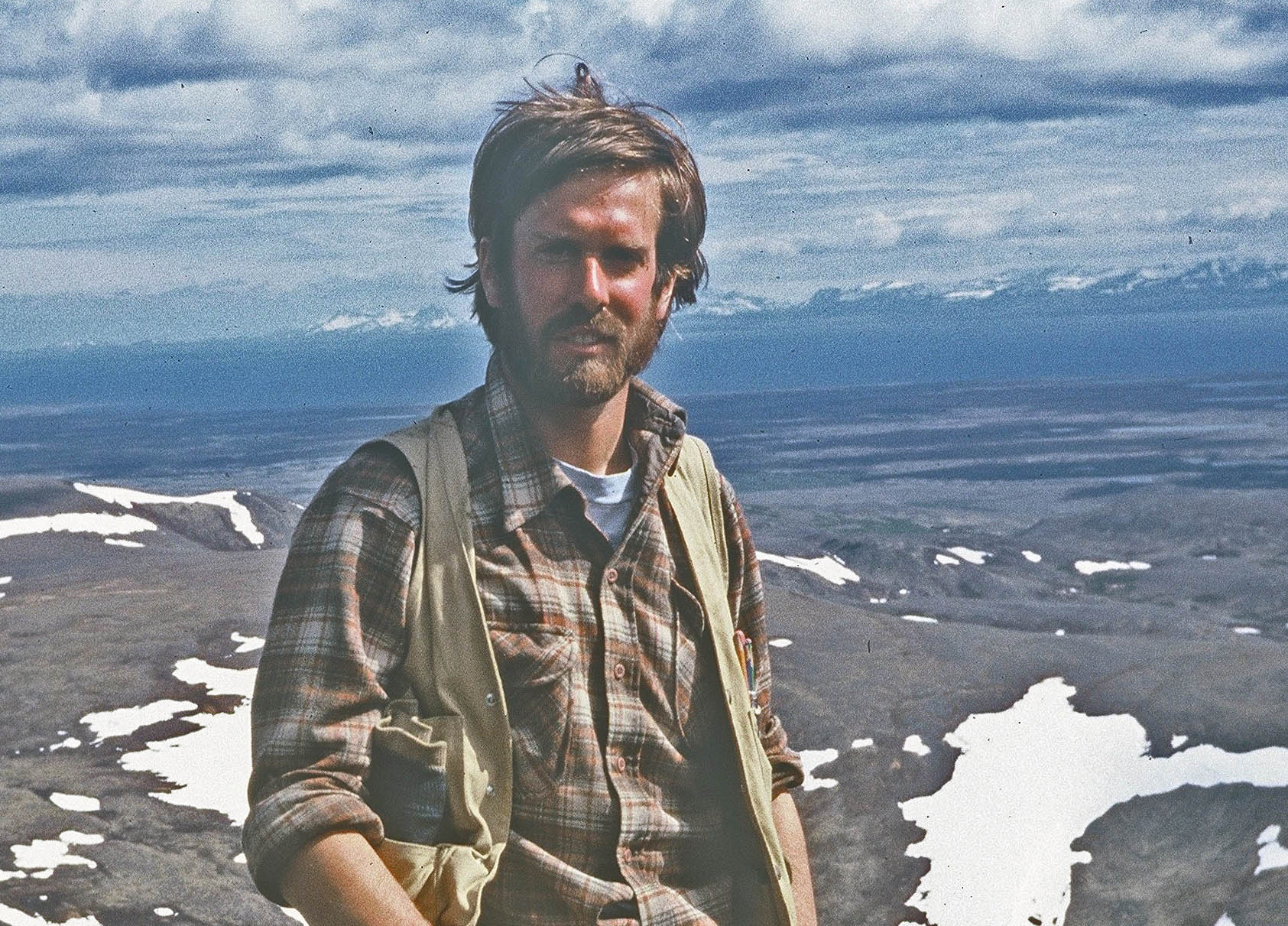

Exploring the relatively flat ground, dotted with small hillocks covered in crowberry, Labrador tea and dwarf birch, was much easier than the team’s usual treks. “We’d been working in extremely steep terrain – holding on to sheer cliffs in the Alaska Range with your fingernails. All of a sudden, walking around on what seemed like golf course terrain, we thought ‘This is awesome! We’re not going to fall to our deaths here!’ ”

“It was kind of dumb to name it Pebble Beach, after a famous golf course,” mused St. George. But the experience was kind of like getting a hole in one, all the same. Indications pointed to the presence of an enormous quantity of gold in the area. And geologic tests, or assays, came back positive for copper too.

“I loved the property from the first sheet of assays I saw, and never stopped loving it,” said St. George.

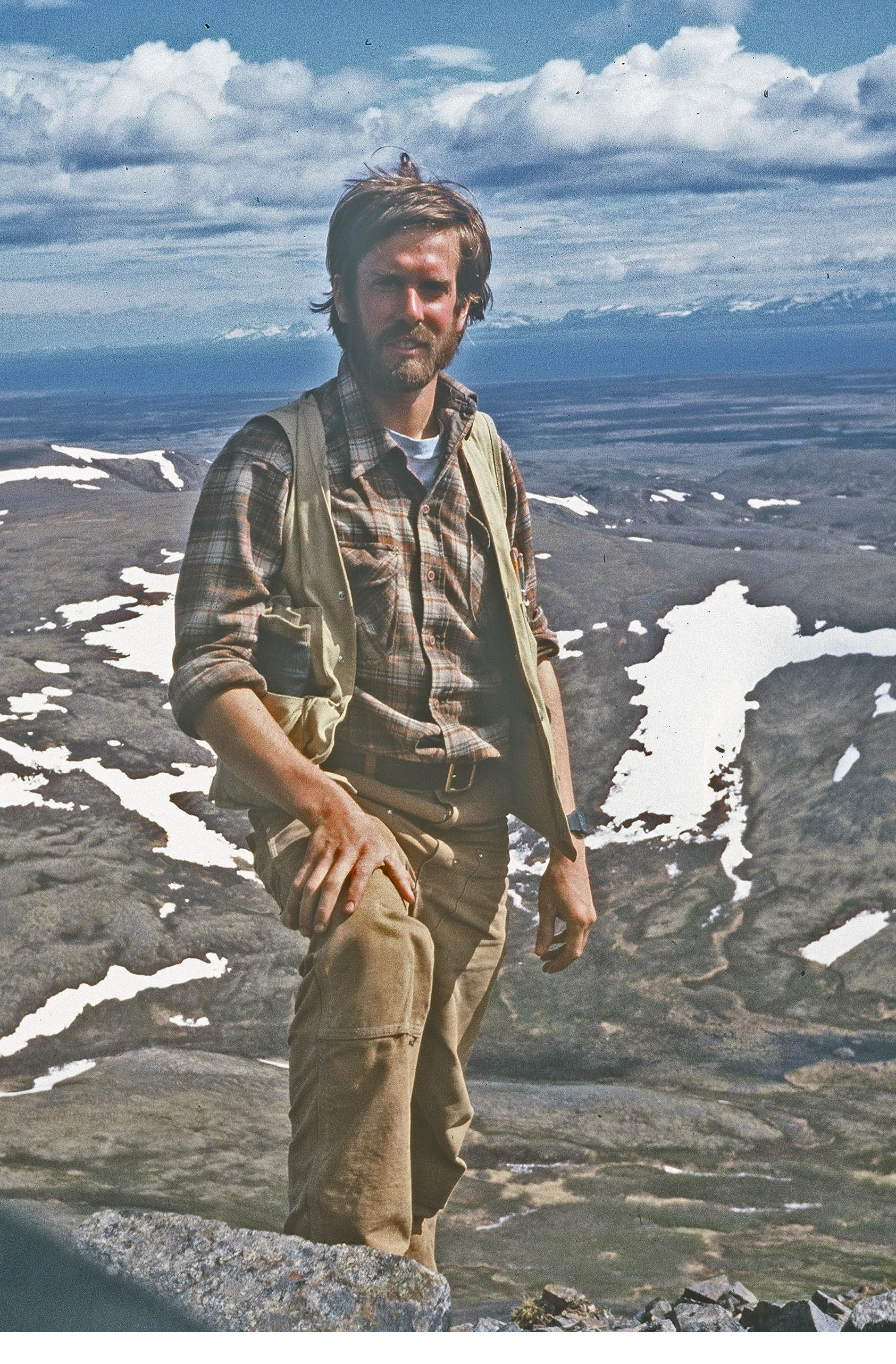

Senior management at Cominco didn’t share his excitement, though, and it was difficult to get funding for drilling. But St. George’s team had also found higher grade gold veins fives miles away from the Pebble site, which gave them the excuse they needed to go back for a closer look.

In 1988, the first two drill holes proved there were higher concentrations of gold at Pebble too. And in 1989, the first copper porphyry mineralization was intercepted. Each season, St. George pounded on tabletops and fought for funding to further the exploration. In all, he drilled out the first half billion tons of the deposit.

During that time period, St. George got more experience looking for copper porphyry deposits. “Cominco wanted to turn me into a porphyry specialist,” he said. He went on mine tours throughout the western U.S. and to South Africa, learning the important aspects of copper porphyries. Deposits are typically surrounded by larger envelopes of altered rocks. Geologists are trained to identify these alterations, which are caused by fluids passing through rock. Being successful as an exploration geologist often means pocketing the hand lens and looking instead at the bigger picture, said St. George. “You have to ask ‘What could be here?’ ‘How big is the area of alteration or mineralization?’

“There is a certain romance for gold. I’ve always liked gold and placer mining. But I always feel better finding copper. It’s something you can’t ignore. It’s a super important metal for mankind.”

Even so, economics are a driving factor in mineral exploration. After a second drilling phase in the 1990s at Pebble, Cominco put the project on hiatus. As St. George explains it, the ore still wasn’t showing a grade (metal concentration) Cominco was interest in. The company was already losing money mining ore valued at $200/ton at Red Dog back then. Pebble would have been worth $50/ton, so it was a losing proposition.

St. George had noticed the grade increasing to the east of the prospect as the deposit dove down below barren volcanic rock, but Cominco managers didn’t want to drill there. Neither did Northern Dynasty Minerals when it acquired the property in 2001. It wasn’t until 2005 that a much higher grade ore was discovered in the East Graben during drilling for theoretical pit walls.

By that time St. George had long since moved on to other Alaska projects, with the Pebble discovery having a big effect on his career. (The name Pebble Beach had given way to “Pebble Copper,” then “Pebble Gold,” and finally just “Pebble”).

“I gave a couple of talks on the discovery and became known as the guy who found Pebble,” said St. George. “There’s some history of ore-finders being successful more than once, and people associate someone who has found a deposit as more likely to find another in the future.”

“I didn’t discover Donlin Creek, but I added 12 million ounces to the resource while working at NovaGold. That’s partly because I had the experience at Red Dog and Pebble and knew what to do.”

St. George said his experience at Red Dog was invaluable. In the 1980s he was a student at University of Idaho in Moscow, where he took a series of courses on ore deposits. He interviewed with Cominco for summer work in Alaska after his sophomore year. “I saw Red Dog before its first drill hole,” recalled St. George. “I can’t emphasize how important it is for someone to see an early stage prospect advance into a mine over a period of time. The experience was huge for understanding what you need to make a mine.”

He said it’s also important to have an open mind, be flexible, and to resist putting square blocks into round holes. “You can never say definitively what’s going on. You have to qualify your statements. You’re just seeing little blocks on the surface.”

Some geologists get a little info and extrapolate it more extensively than what they have information for, noted St. George. He likens it to the story of the blind men with an elephant. The one who touches the tusk thinks it’s a pipe. The one touching an ear thinks it’s a big fan. The one touching the tail thinks it’s a snake. And they are all wrong. “People that think they know exactly what’s going on are rarely spot on in this field,” said St. George. So having natural curiosity is important to be a successful exploration geologist. “There’s so much to learn that you need to feed on any info you can get. Any information can be valuable without even recognizing it.”

These days St. George is Chief Exploration Officer at Millrock Resources, a project generating company he founded with Greg Beischer in 2007. “When we started Millrock, his reputation was clearly beneficial,” said Beischer. “People invested in part because he was well-known as a deposit discoverer and geologist who had found a lot of ounces of gold.”

Over the years, St. George worked throughout the Alaska Interior, Seward Peninsula, Alaska Peninsula, Bristol Bay, the Alaska Range, and saw a lot of beautiful countryside. “It’s been a wonderful job, and I’ve seen and found some amazing things,” he said.

One thing in particular makes Alaska really special, he explained: it’s the biggest state in the U.S. and probably getting bigger for more time to come. “Oceanic plates landing in Alaska have made it grow and grow and grow. There have been many different periods of ore deposition, melting down oceanic plates, and all kinds of different metals come up from these continental plates. It’s a well-endowed area because of this continuous subduction for over 200 million years.”

But exploration geologists interested in working in Alaska should know about some of the state’s other distinctions too. St. George has countless bear stories, and remembers “waking up from a field nap with a bear walking toward me.” Once he saw a black bear as big as a large brown bear that “had to be eating a pure fish diet to get that big.” With 80 to 100 days in the field each year, St. George also collected some wolverine stories, and recounts that “beating through alders all day in rain, and mosquitos in the Brooks Range rank up there with some of the more unpleasant moments.”

Some of the more pleasant memories have to do with the people he met along the way. During the early years exploring the Pebble deposit, work operated from Myrtle and Elia Anelon’s housing complex in Iliamna, said St. George, who came to know their children and grandchildren. “The grandchildren had the impression my name was ‘Cominco,’ as they probably heard Cominco was coming to town and they knew I was the project manager!”

He also met his wife Laura by hiring her to cook at the Pebble exploration camp in 1989. “We hit it right off, as I let her beat me in pool and we both enjoyed each other’s company. We weren’t in town for more than a day or so and the Anelon grandchildren recognized that we liked each other. So, they started singing ‘Phil and Laura kissing in a tree, K-I-S-S-I-N-G, first comes love, then comes marriage then comes a baby in a baby carriage!’ This of course, quickly informed the entire crew that we were in a relationship, that and the fact that I was helping her clean the dishes. There is no hiding secrets in an exploration camp. In fact there was a saying in Iliamna that if you went into a dark closet and had a thought to yourself, as soon as you came out of the closet the entire town of Iliamna knew what you were thinking!” Phil and Laura got married a year and a half later.

After decades in Alaska, they relocated to Arizona in 2015 in search of sunnier weather. These days, in addition to his work with Millrock Resources, St. George enjoys explaining the geologic wonders of Arizona State Parks on guided walks. Laura likes to give him any heart-shaped rocks she finds. They are all placed in the rock garden to honor a strict family rule that could well be a secret to marital harmony for all geologists: no rocks in the house!

While he’s thousands of miles away from Alaska, St. George still thinks about the Pebble deposit. “It’s like loving your child. You want it to come to fruition. Geologists develop an emotional attachment to properties they put a lot of work and sweat in to,” he said.

“Discovering a deposit is great,” added Beischer. “But a geologist’s ultimate goal is to discover a mine. The reality is hardly any geologist actually achieves that goal. It’s so rare to discover something that goes all the way to production.”

For more a more detailed history of the Pebble deposit discovery, read this summary written by Phil St. George.

While Phil St. George has been credited with the discovery of the Pebble deposit, he acknowledges the work of several people whose efforts led to the exploration of the area. They include: Joe Piekenbrock, Roy McMichael, Helen Farnstom Roberson, Tim LaPorte, Lorne Young, Rich Moses, John Robinson, Laura Gould, Paul Weatherbee, Kent Turner, and Myrtle and Elia Anelon.